- Nov 20, 2025

Less Than 1 Percent of UK Doctors Prescribe Medical Cannabis

- Global Cannabinoid Solutions

- 0 comments

Understanding the Structural Misalignment and the Opportunity Ahead

By Global Cannabinoid Solutions

Global Cannabinoid Solutions | 2025

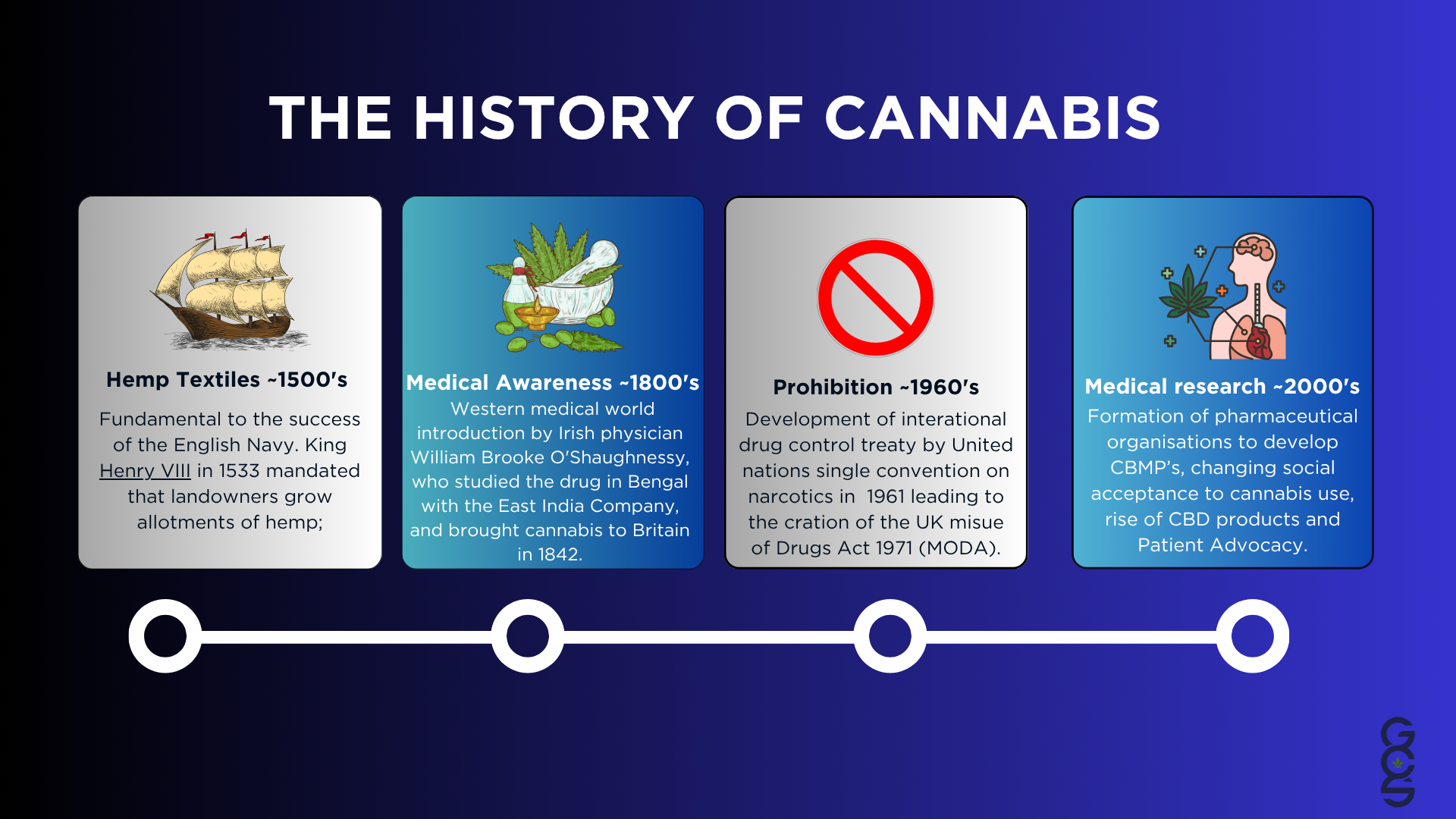

According to recent reporting from Leafie (O’Dowd, 2025), it is estimated that fewer than 1% of doctors on the UK’s GMC Specialist Register have completed the required training to prescribe medical cannabis. This statistic has persisted for years despite growing patient interest, expanding private sector access, and a rapidly advancing scientific understanding of cannabinoid pharmacology and the endocannabinoid system.

This limited clinical participation is often attributed to stigma, insufficient education or unfamiliarity. While these factors play a role, they do not provide the full explanation. The deeper issue arises from a structural misalignment between how cannabis functions as a complex botanical therapy and how the modern medical system evaluates, regulates, and adopts new treatments. A medical infrastructure built for single-compound pharmaceuticals struggles to accommodate a therapeutic intervention composed of dozens of synergistic molecules that interact with a widespread regulatory system.

This article examines the roots of this misalignment, the limitations of classical trial structures, the role of real-world evidence, and the broader implications for innovation, safety, and the future of cannabinoid medicine in the UK.

1. A Medicine That Does Not Fit the Mold

Modern medical frameworks developed alongside synthetic pharmacology. Clinical trials, prescribing protocols, regulatory pathways, pharmacovigilance systems, and educational structures were designed with the assumption that medicines are stable chemical entities, each with a small number of mechanistic targets and predictable dose-response curves.

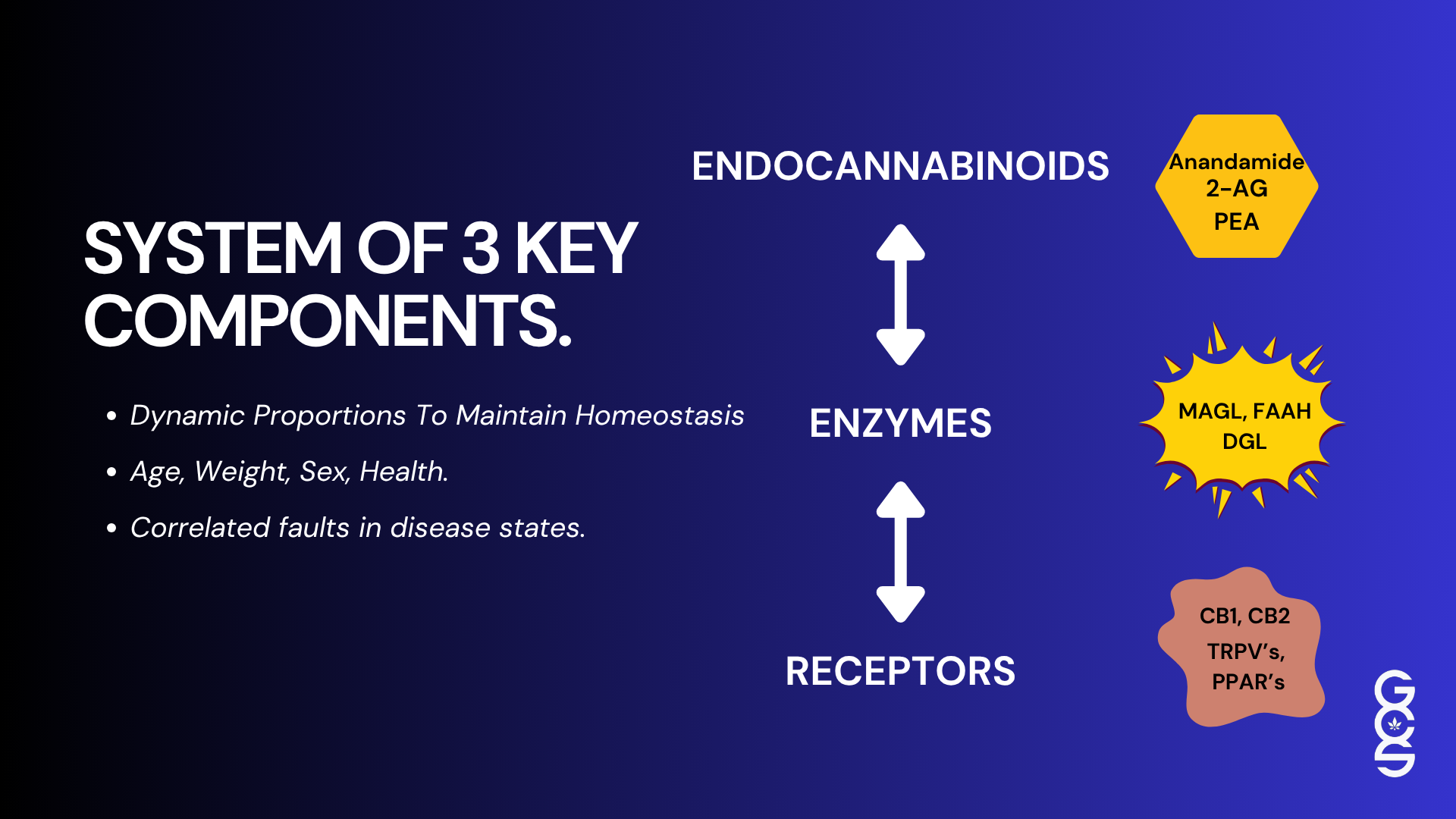

Cannabis does not conform to this model. It contains more than 120 identified cannabinoids along with a substantial number of terpenes, flavonoids and other secondary metabolites. These compounds do not act in isolation. They influence one another and they often exert effects through multiple physiological pathways.

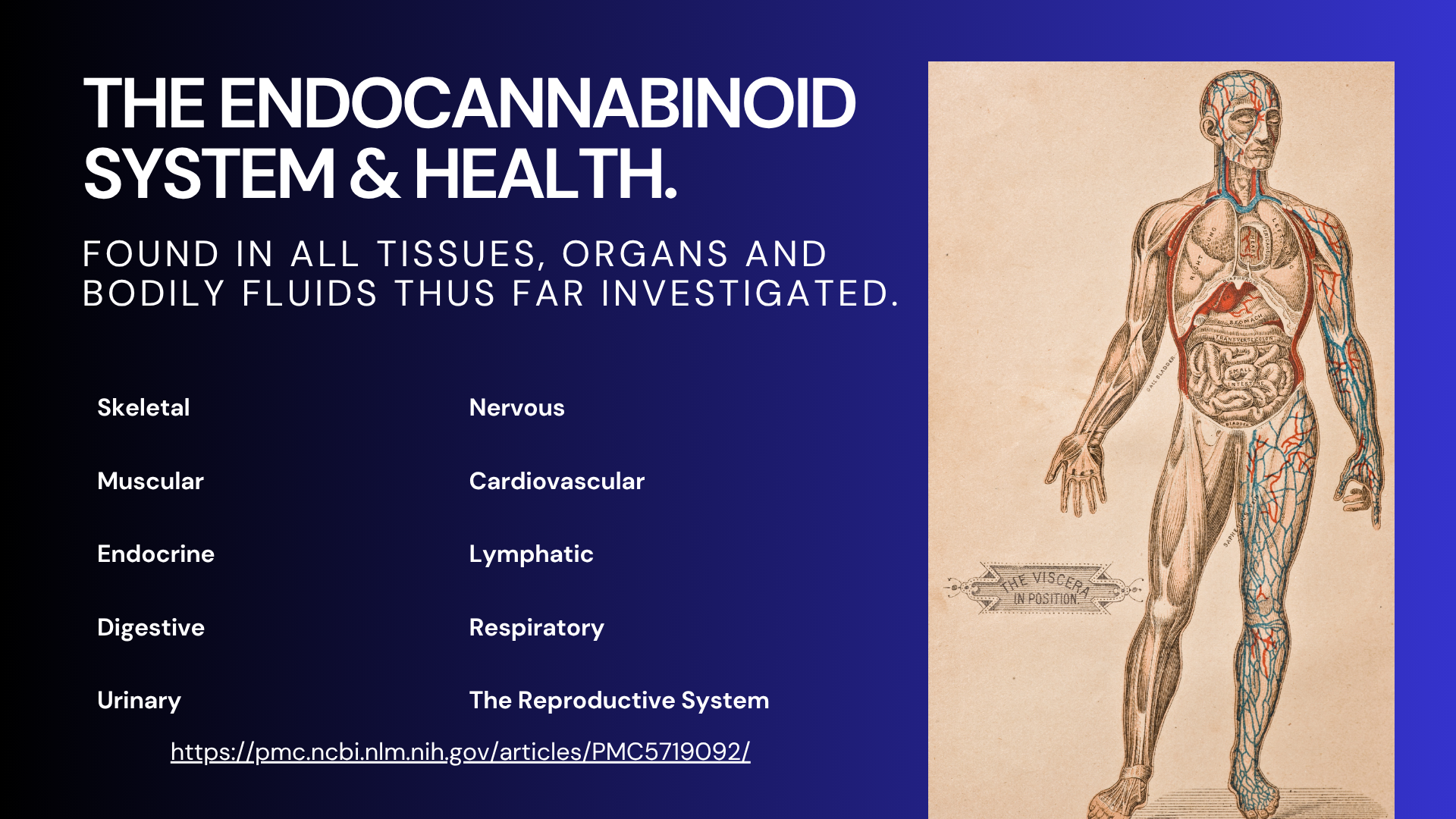

Central to cannabis activity is the endocannabinoid system, which is present in every bodily tissue and fluid studied thus far. The ECS regulates processes that include emotional state, sleep, immune activity, pain modulation, inflammation, metabolic balance and stress recovery. Because cannabis interfaces with such a broad and integrative system, its effects are inherently multidimensional and context-dependent. Evaluating this type of therapeutic system using tools created for isolated pharmaceuticals compresses complexity into an ill-fitting structure.

“Endocannabinoid signalling has been identified in all tissues, organs, and bodily fluids studied so far.”

Hillard CJ. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018.

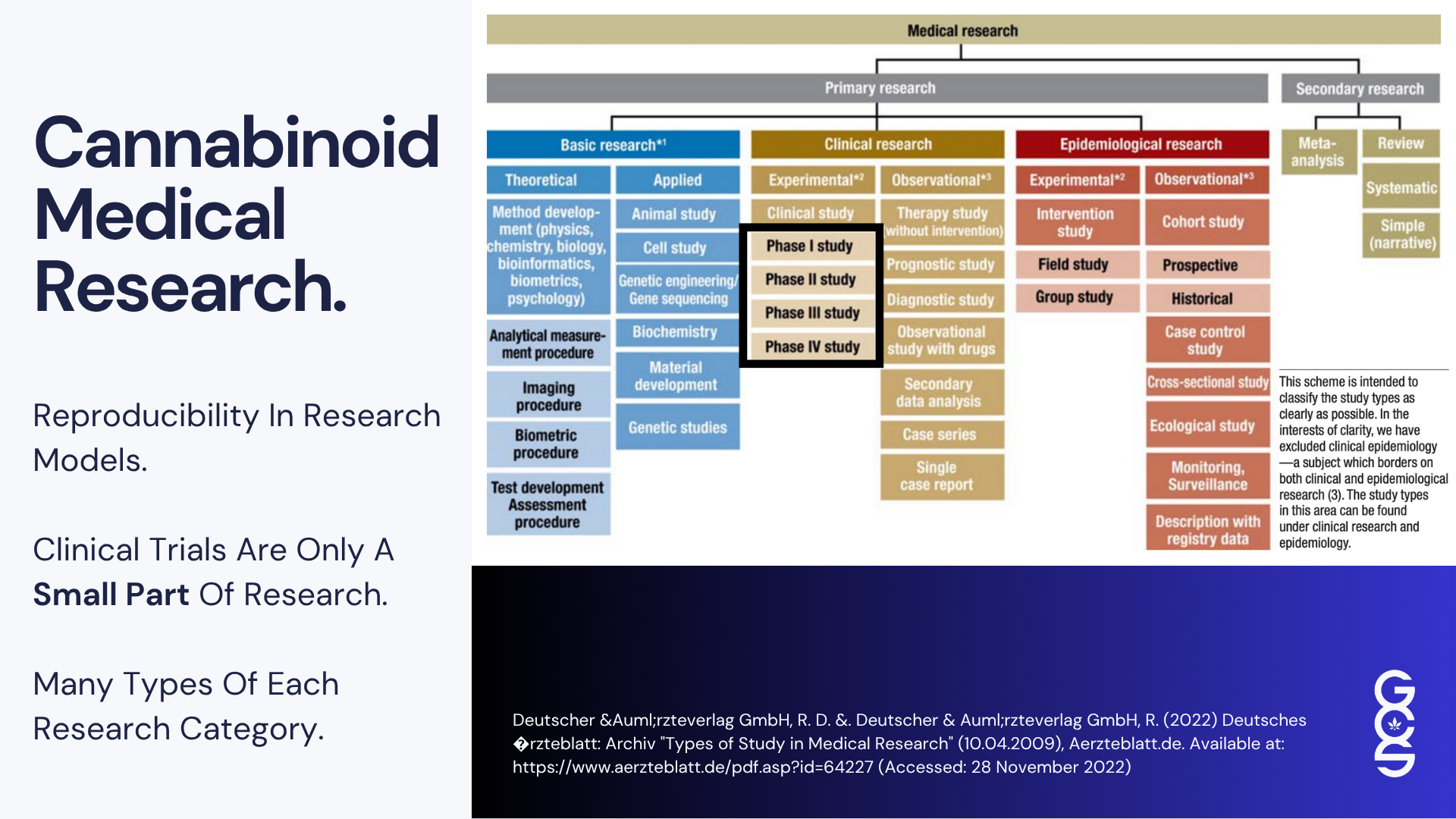

2. Why Traditional Clinical Trials Struggle to Represent Cannabis

Randomised controlled trials remain essential for establishing safety and identifying pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic boundaries. However, the features that make RCTs ideal for synthetic molecules often limit their ability to reflect the behaviour of cannabis.

RCTs depend on fixed dosing, consistent timing, minimised variability, specific endpoints and controlled environments. These constraints reduce noise and isolate the effect of a single compound. Yet cannabis works differently. Its effects depend on gradual titration, differences in tolerance, variability in product chemotype, and the influence of lifestyle variables that include sleep, diet, physical activity, stress exposure, emotional context and routine.

When these factors are suppressed in pursuit of experimental purity, the trial environment eliminates components of the therapeutic mechanism itself. In many trials, cannabis appears less effective or less consistent not because the intervention is weak, but because the methodology removes the context required for the therapy to express its true potential.

“Pharmacological manipulation of the ECS has gained significant interest… offering promising opportunities for the development of novel therapeutic drugs.”

Lowe H et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2021.

Pharmaceuticalised cannabis extracts such as nabiximols demonstrate efficacy under RCT conditions because they conform more closely to the single compound model (Wade et al., 2004; Collin et al., 2007). Whole plant cannabis, by contrast, operates in a fundamentally different way and therefore requires a broader, more adaptive evidence framework.

3. Real World Data and Why Cannabis Needs It

Real-world data captures the way interventions behave outside controlled research settings. For cannabis, this type of evidence is essential. It reflects long-term changes in sleep, pain variability, mood, stress response, functional mobility and daily life performance, which patients consistently describe as their most significant improvements.

Real-world data also reflects dynamic dosing patterns, shifts in product preference, patient-led experimentation, tolerance changes, and the influence of social and environmental context. These features are central to cannabis therapy yet absent from controlled trials.

“Phytocannabinoids interact with metabotropic receptors, ionotropic channels, and transcription factors, offering access to a promising and diverse pharmacological space.”

Hanuš LO et al. Nat Prod Rep. 2016.

Where controlled trials reveal specific outcomes and mechanistic clarity, real-world evidence reveals ecological validity. The two forms of evidence do not compete. They complement one another and together offer a fuller understanding of cannabis as a therapeutic system.

4. Human Variables and the Diversity of ECS Responses

Human biological variation plays a decisive role in shaping responses to cannabis. Unlike therapies that act through narrow molecular pathways, cannabinoids interface with the endocannabinoid system, a regulatory network that is inherently dynamic and deeply influenced by both internal physiology and external environment. This means that the ECS does not behave the same way in every person, and as a result, cannabis outcomes can vary significantly even when patients use identical products at identical doses.

“The ECS is a critical signalling network deeply embedded throughout the brain and body, regulating core functions such as mood, stress, immune response, neuroplasticity, and development.”

Reddy V et al. EPMA Journal. 2020.

Genetic differences contribute substantially to this variability. Polymorphisms in ECS-related genes, such as those influencing CB1 and CB2 receptor expression, FAAH and MAGL enzyme activity, and endocannabinoid production, can alter sensitivity to cannabinoids, duration of effect and overall therapeutic response. Individuals with decreased FAAH activity, for example, may have higher baseline endocannabinoid levels and therefore require different dosing compared with individuals who metabolise endocannabinoids more quickly.

Lifestyle variables also exert considerable influence. Diet, particularly the presence or absence of dietary fats, directly affects cannabinoid absorption because cannabinoids are lipophilic. Sleep quality and circadian rhythm modulate ECS tone, with poor or inconsistent sleep often contributing to lower endocannabinoid availability. Stress, both acute and chronic, is one of the most powerful modulators of ECS signalling, altering receptor density and shifting neurotransmitter balance in ways that influence how cannabis is experienced.

Metabolic differences further affect cannabinoid processing. Liver enzyme activity varies widely across populations, from individuals with rapid metabolism who process cannabinoids quickly to those who metabolise them slowly, producing prolonged or intensified effects. Age also plays a role. Younger adults often display more robust ECS responsiveness, while older adults may experience altered receptor density or delayed metabolic clearance.

The emotional and psychological context adds yet another layer. The ECS regulates stress recovery, emotional processing and fear extinction, meaning that cannabinoids often interact with a person’s immediate psychological environment. The same dose that produces calm in one context may feel sedating or overwhelming in another, not because the product has changed but because the internal state has shifted.

Previous cannabinoid exposure shapes tolerance and responsiveness. Individuals with long-term exposure may require higher doses or experience different subjective effects due to adaptation within the ECS. Those new to cannabinoids may respond more strongly or more unpredictably until a personalised baseline is established.

Clinical environment also matters. Studies consistently show that being observed, monitored or assessed can change behaviour, sleep patterns, stress levels and overall response. Controlled trial settings, therefore, often produce different outcomes from those observed in natural environments where patients use cannabis as part of daily life.

All these variables illustrate that cannabis does not behave as a fixed intervention applied to a homogeneous human biology. It interacts with a personalised, shifting regulatory system that integrates genetics, lifestyle, behaviour, emotions, environment and time. A medical model that expects uniformity of response will inevitably misinterpret a therapy whose mechanism depends on diversity. Recognising this complexity is not a barrier to scientific progress. It is the foundation for understanding cannabis accurately and designing evidence frameworks that reflect real human physiology rather than idealised laboratory conditions.

5. Clinical Trials and Real World Data, Two Evidence Worlds That Must Evolve Together

Cannabis sits between two evidence paradigms, and each contributes something essential while leaving gaps the other must fill. Clinical trials provide structure, controlled observation, standardisation and mechanistic insight. These elements are vital for determining safety, identifying contraindications, and understanding pharmacological interactions. Without RCTs, cannabis could not be responsibly integrated into clinical care.

However, cannabis does not behave like a pharmaceutical designed to produce uniform responses. Its effects unfold over time, often through subtle shifts that accumulate gradually. Improvements in sleep continuity, reductions in symptom volatility, stabilisation of emotional states and enhanced functioning at home or work may represent the most meaningful benefits for patients. These functional improvements are rarely captured by traditional trial endpoints focused on short-term symptom change.

“Minor phytocannabinoids… interact with CB1, CB2, TRP channels and more — each demonstrating therapeutic roles in pain, epilepsy, cancer, and neurodegeneration.”

Caprioglio D et al. Pharmaceuticals. 2023.

Real-world data can reveal these longer-term effects clearly. It shows how cannabis interacts with daily routines, life stressors, sleep cycles and personal environments. It also illustrates how treatment evolves as patients adjust dose, timing and product choice.

Neither form of evidence alone is adequate. If the field relies on RCTs alone, cannabis will always appear narrower, less effective and less predictable than it is in reality. If the field relies on real-world evidence alone, the therapy cannot be regulated responsibly. The two systems must be integrated into a more balanced evaluation model in which RCTs establish safety and pharmacological foundations, and real-world evidence characterises functional benefit and therapeutic reality.

Cannabis may eventually help reshape medical science by revealing that the future lies not in rigid hierarchies of evidence, but in a pluralistic model that recognises the strengths and limitations of each method.

6. A Structural Mismatch That Suppresses Innovation and Creates Risk

The extremely low rate of clinician prescribing does not indicate disinterest. It reflects a deeper structural mismatch. Strict medical systems struggle to adopt therapies that fall outside pharmaceutical patterns. When evidence frameworks demand mechanistic precision, fixed dosing, biochemical uniformity and rapid symptom reduction as prerequisites for legitimacy, cannabis simply does not fit the template. This rigidity suppresses innovation. It discourages clinicians from exploring therapies that behave differently, and it prevents entire categories of treatment from gaining traction.

However, excessive flexibility is also dangerous. A permissive environment with little structure introduces risks, including inconsistent product quality, variable dosing, inadequate monitoring, uneven clinical practice and incomplete safety oversight. If systems become too loose, the field becomes vulnerable to non-evidence-based claims, and patient care suffers.

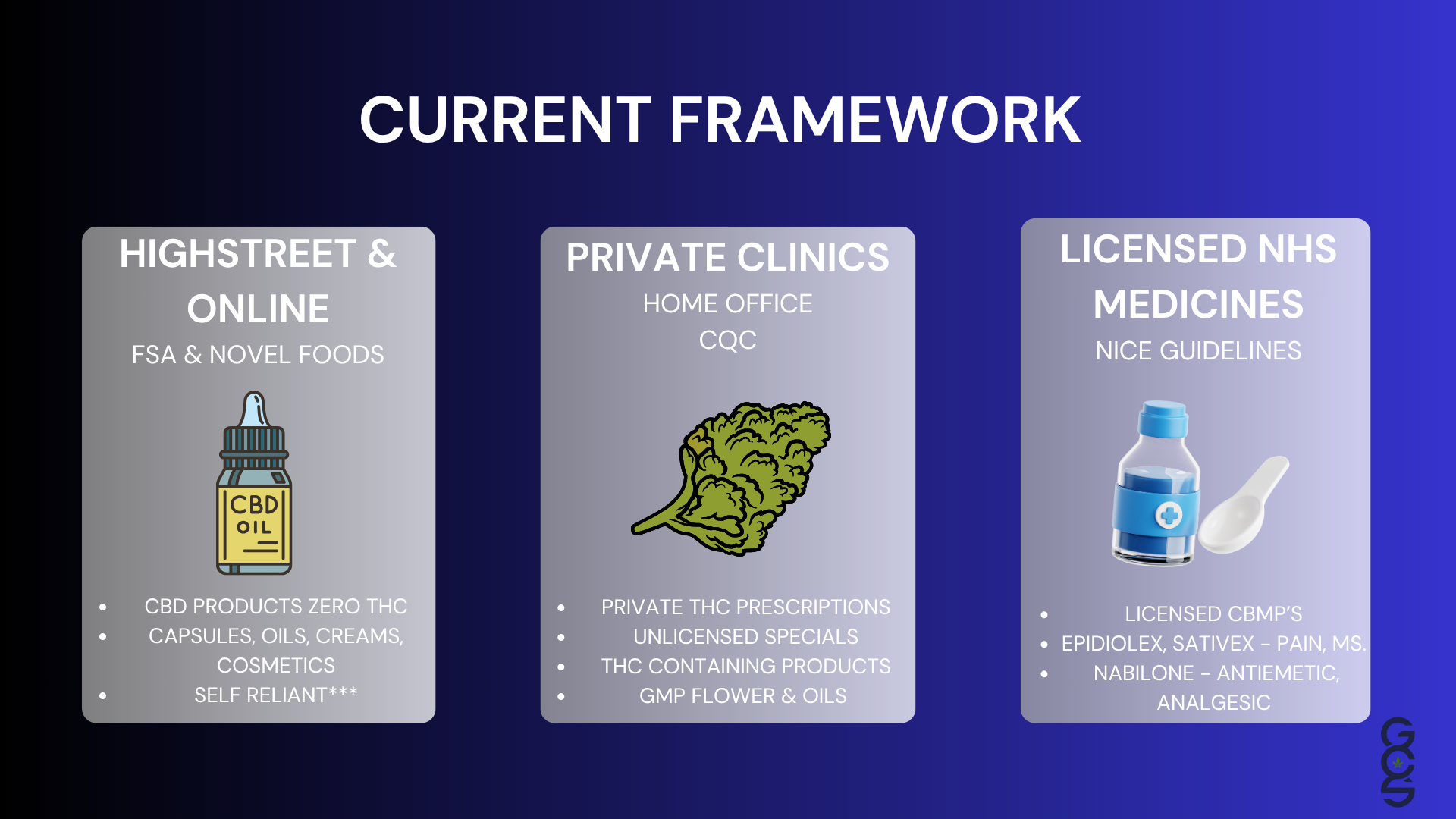

Cannabis exposes both weaknesses at once. It highlights what happens when evidence systems become too narrow and when regulatory frameworks become too permissive. The UK’s current landscape reflects both extremes. The NHS remains almost entirely closed to cannabis due to rigid evidentiary expectations. The private sector, although pioneering, sometimes lacks the consistent structure required for a medicine with significant therapeutic potential.

The future demands balance. A mature cannabis ecosystem requires standards strong enough to protect patients but flexible enough to allow innovation, regulatory models that recognise complexity rather than avoid it, and clinician training that moves beyond single-molecule paradigms. Without this balance, cannabis will remain marginalised on one side and inconsistent on the other.

7. When Narrow Evidence Systems Overlook Innovation

When healthcare systems rely on narrow evaluation methods, particularly those that prioritise quick, isolated changes measured over short periods, they risk overlooking therapies whose benefits accrue gradually or manifest in broader functional domains. Cannabis exemplifies this challenge. Many of its most meaningful effects emerge in areas that traditional clinical endpoints were not designed to measure.

Patients frequently report improvements in sleep quality, emotional resilience, daily functioning, stress tolerance and symptom stability. These multidimensional outcomes may not produce dramatic shifts on standardised symptom scales within four or eight-week trial windows. Yet, from a patient perspective, these improvements can significantly alter overall well-being.

If evidence systems only recognise outcomes that fit within narrow methodological categories, innovative therapies that function through holistic or longitudinal mechanisms are at risk of being undervalued. This slows scientific progress and reduces opportunities for patients who may benefit from alternative or adjunctive therapies.

Expanding evidence frameworks does not dilute rigour. It increases precision by acknowledging that therapies can produce multiple forms of benefit and that meaningful health outcomes extend beyond short-term symptom suppression.

“Pharmacological manipulation of the ECS… offers promising opportunities for the development of novel therapeutic drugs.”

Lowe H et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2021.

8. The Private Sector, Its Challenges, Progress and Clinical Significance

Because so few NHS clinicians are trained to prescribe cannabis, the private sector has become the central environment in which cannabinoid based medicine is actively practised. This has created both challenges and remarkable progress.

Operational consistency varies significantly between clinics. Some demonstrate robust scientific alignment, careful patient monitoring and strong clinical governance. Others have been slower to adopt consistent protocols. This variability, while common in emerging sectors, highlights the need for unified standards to ensure safety and reliability.

Despite these challenges, the private sector has become the birthplace of genuine clinical expertise. A growing cohort of clinicians now understands cannabinoid pharmacology at a depth rarely found elsewhere in the UK. They recognise the importance of personalised titration, product chemotype, patient-specific variability, long-term monitoring and functional outcome tracking. They understand the distinctive behaviour of whole plant therapeutics and apply this knowledge in patient-centred ways.

This group of clinicians offers a preview of what a more mature cannabinoid medical system could become. Their experience shows that with adequate training, careful oversight and consistent evaluation frameworks, cannabis can be delivered safely, ethically and effectively within clinical practice. This growing expertise represents the seeds of the future cannabis clinical community across the UK.

9. The Future, A Modern Evidence Ecosystem Built on Science, Safety and Patient Centred Innovation

Cannabis challenges healthcare to evolve. It reveals that human health is complex, multidimensional and influenced by interactions between biology, behaviour, environment and time. Evidence systems must therefore become more adaptive and more capable of evaluating therapies that behave outside conventional pharmacological norms.

A modern evidence ecosystem for cannabis should integrate controlled research with real-world insight, embrace the diversity of human biology, and support clinicians in using personalised, responsible approaches. This does not replace conventional medicine. It strengthens it. It expands its capacity to understand complex therapeutics and to serve patients whose needs may not be fully addressed by traditional pharmaceuticals alone.

The leaders of the next decade will be those who combine scientific nuance with ethical practice, who recognise the value of both reductionist and holistic evidence, and who can guide patients safely through therapies that require careful titration and ongoing evaluation. The future of cannabinoid medicine in the UK will be shaped not by rigid adherence to outdated frameworks or unstructured permissiveness, but by intelligent integration of diverse evidence systems.

Cannabis does not ask medicine to abandon rigour. It asks medicine to modernise it.

Explore Further, Free Education

For those seeking deeper understanding of cannabinoid science, the ECS and the evolving evidence landscape, Global Cannabinoid Solutions offers a free digital training.

Watch our Cannabinoid Medicine Induction Course:

https://www.cannabissciencetraining.com/cannabinoid-medicine-for-healthcare-professionals

References

O Dowd, S. (2025). Fewer than 1 percent of UK doctors trained to prescribe medical cannabis. Leafie

Collin, C., Davies, P., Mutiboko, I. K., and Ratcliffe, S. (2007). Randomized controlled trial of Sativex in multiple sclerosis spasticity. European Journal of Neurology, 14

Wade, D. T., Makela, P., Robson, P., House, H., and Bateman, C. (2004). Effects of cannabis based medicinal extracts on symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Clinical Rehabilitation, 18

Hillard, C. J. (2018). Circulating Endocannabinoids: From Whence Do They Come and Where Are They Going? Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(1), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2017.130

Lowe, H., Toyang, N., Steele, B., Bryant, J., & Ngwa, W. (2021). The Endocannabinoid System: A Potential Target for the Treatment of Various Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(17), 9472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179472

Hanuš, L. O., Meyer, S. M., Muñoz, E., Taglialatela-Scafati, O., & Appendino, G. (2016). Phytocannabinoids: A Unified Critical Inventory. Natural Product Reports, 33(12), 1357–1392. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6NP00074F

Reddy, V., Grogan, D., Ahluwalia, M., et al. (2020). Targeting the Endocannabinoid System: A Predictive, Preventive, and Personalized Medicine-Directed Approach to the Management of Brain Pathologies. EPMA Journal, 11, 217–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13167-020-00203-4

-

Caprioglio, D., Mattoteia, D., Mandolini, G., et al. (2023). Minor Phytocannabinoids: A Misleading Name but a Promising Future. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 16(5), 651. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16050651

- Free

The Lab

- Includes 5 additional products